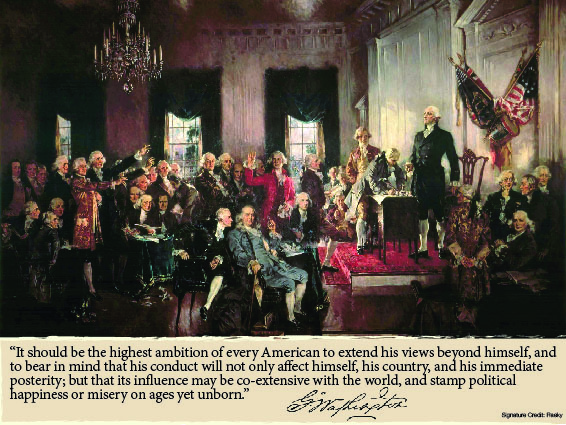

In 1776, America conducted a revolutionary experiment. The Founding Fathers of America set forth an ambitious vision. When monarchies were the choice form of governance, they set out to prove that a government could be run “of the people, for the people and by the people”.

In 1776, America conducted a revolutionary experiment. The Founding Fathers of America set forth an ambitious vision. When monarchies were the choice form of governance, they set out to prove that a government could be run “of the people, for the people and by the people”.

However, the experiment took more than just inspired individuals proposing a vision; it took men and women of character whose careful conduct brought the vision to life. This is the importance of precedents.

Dr. Moon recently commented, “If there were no George Washingtons, Thomas Jeffersons, and Madisons, if there were no Abraham Lincolns, the American experiment would have failed many times over.”

These presidents defined and upheld the moral and ethical principles necessary for America’s growth. In his farewell address, George Washington, first President of the United States acknowledged the critical importance of morality for the longevity of the nation, “Tis substantially true, that virtue or morality is a necessary spring of popular government.”

Fondly referred to as the father of his nation, Washington set the course of the nation in many ways.

Monarchy or Republic

It could be said that Washington’s firm commitment to the republican experiment secured America’s future as a republic and not a monarchy.

In the early discussions of American independence there was a significant opinion that American should become a monarchy. Lewis Nicola, one of Washington’s officers, wrote to Washington in 1782, suggesting that Washington become King of the United States. Washington firmly reprimanded Nicola. “Banish these thoughts from your mind, and never communicate, as from yourself, or anyone else, a sentiment of the like nature.”

From the beginning Washington shied away from position, only stepping up to fulfill his duty as a public servant. He accepted the Presidency with humble deference to the “public summons” of the people and the will of the “Almighty being”.

He declined titles such as “Your Excellency” and “Sir” and took the simple title “Mr. President”. In his inaugural address, Washington even refused a salary, which he later accepted after being advised that a salary would dispel the image that only wealthy, self-supporting individuals could run for office.

Washington agreed to a second term only after he was convinced that he could help quell the partisan rift that threatened the fledgling nation. After serving a second time, he gracefully retired, even amidst calls for a third term.

His selfless service to the public can still inform public servants today.

Liberty of Conscience

On several occasions, Washington expressed that, “…reason and experience both forbid us to expect that National morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.” For Washington, religion was the foundation for virtue, a critical ingredient to making the republic function. He also believed that most religions shared fundamental principles. To this end, he protected liberty of conscience and freedom of religious practice.

Shortly after his first election, George Washington wrote a letter to the Hebrew Congregation in Newport, Rhode Island that has become a timeless affirmation of the United States’ commitment to religious freedom. “The Government of the United States, “ he wrote, “gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens…” In his farewell address he urged Americans to recognize and be proud their common national identity, describing religious, cultural and political disparities as “slight shades of difference”.

Religious freedom is significant achievement of the United States of America.

Conclusion

Today, Washington ranks among the three most respected presidents. (89% view him favorably according to public policy polls.)

His precedents gave substance to the principles and values that formed the vision of the American experiment–that “all men are created equal and endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights” and a government is called to protect and secure these rights.

Washington was keenly aware of the impact of his actions on future Americans. He said, “It should be the highest ambition of every American to extend his views beyond himself, and to bear in mind that his conduct will not only affect himself, his country, and his immediate posterity; but that its influence may be co-extensive with the world, and stamp political happiness or misery on ages yet unborn.” (Pennsylvania in 1789)

Any worthwhile vision needs men and women of character who set precedents that bring it to life.