International students perform “chul”, a formal greeting of deep respect reserved for the elderly of a family to local “grandparents” on New Years.

The importance of filial piety in Korean society has been a topic of scrutiny and discussion for decades, if not centuries. The parent-child relationship is valued in Korea to an extent that distinguishes itself even among the East Asian nations. Stories on the theme of filial piety abound in Korean’s beloved folklores and collective psyche. During the Chosun dynasty, the government officially rewarded acts of filial piety and devotion. And no less a scholar than the veritable Arnold Toynbee noted that, “the Korean [teaching] of hyo, their practice of respecting the old and the traditional family system are one of the finest among existing thoughts in the world.”

Yet, a 2014 Washington Post article notes that “Over the past 15 years, the percentage of children who think they should look after their parents has shrunk from 90 percent to 37 percent, according to government polls.” While the reasons for this dramatic shift in attitudes towards the elderly are unclear, the poverty, neglect and astonishingly high suicide rates among the elderly in South Korea are dismal indicators of this trend. The elderly in South Korea that once led the intense economic “miracle on the Han River” now ironically suffers the highest poverty rates among the OECD nations at 49.3 percent in 2012. Government efforts to curb senior suicides include a “well-dying“ class but does not address the wider social issue of the attitudes and norms of the greater Korean society towards their own elderly.

The Global Peace Foundation Korea regularly sends volunteers to socialize and feed the elderly. The situation of Korea’s silvering population is the subject of many social critiques.

In the Korean Dream book, the downward spiral in Korea’s social norms and the loss of a once most highly prized virtue is rooted in a loss of identity and to the detriment of Korean society overall. Cutthroat competition, intense ambition, and materialistic overindulgence in South Korea has contributed to a more general disregard for others, especially the most needy. This has, in turn, led to appalling incidents such as highly publicized Sewol Ferry tragedy in 2014. In the North, we see the dehumanizing effects of an absolute autocracy based in an atheistic materialism that has little regard for human beings or relationships. The development of these two systems might be first attributed to the years of Western cultural influence, the traumatic Korean War and the oppressive Japanese colonial occupation before that.

In light of all these factors and to reverse current trends, it is natural to suggest a return to what came before – to the Korean cultural heritage dating back 5,000 years. It is of crucial importance that this is not a return to an illusory golden past but rather a return to the highest aspirations and ideals that have sustained the Korean people throughout history. These ideal are – in short – found and enshrined in the Tangun story and the principle of Hongik Ingan.

In our first exploration of the Tangun story, we looked to the Korean sense of human dignity as grounded in the Divine. Here we look to Tangun and his father, Hwannug and the significant expressions of filial piety interwoven throughout both of their stories. Here the idea of filial piety is implied rather than stated and tied to the Korean concept of the self not as an individual but as a continuity of others as discussed in this piece on the Korean use of the word “uri“. One assumes that Hwannug’s wish to implement and emulate on earth the rule of his father in the Heavens is expressive of honor and respect for his father. Even in a cursory study of relationships between fathers and sons one observes the aspiration of a son to bring honor and pride to the father.

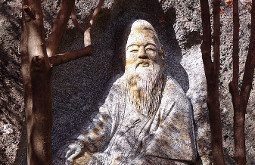

The founding three generations of Gojeoson are enshrined in Samseonggung on Mt. Jiri: Hwanin, Hwannung and Tangun.

In the Tangun story, Hwannug was moved by compassion for the people of earth and requested to come down from Heaven in order to manifest the Lord of Heaven’s principles on earth. Tangun then established a kingdom based on the wishes of his father to govern from truth, and bring broad benefit to humanity and honor to both Hwannug and Hwanin. In marked contrast to what we might view as ‘human nature’, Hwannug and Tangun are seen as the highest examples of filial piety in their drive to serve the greater good for all humanity.

We also see facets of this thought in Korean culture, where filial piety or the way of filial piety (효도, hyodo) is more than a relationship or a feeling but is a concept substantiated through accomplishments. As mentioned earlier, the Korean sense of devotion to parents is frequently linked to the personal ambition to bring honor to one’s parents and ancestors. For Hwannug and Tangun, fierce ambition is not for self-aggrandizement but to pay homage to their forefathers and to bring benefit to humanity; thus ambition and filial piety take on a noble quality.

And while some may attribute the Korean emphasis on filial piety (孝, 효) to Confucianism, Confucius himself laid no claim to the ideals he taught but rather acted to articulate what were universal truths ascertained through deep engagement with the wisdom of the ancestors as well as a close “investigation of things.” Moreover, while both the Chinese and Japanese societies have taken up Confucian teachings, neither society emphasizes the values of filial piety and familial devotion in quite the way Korean society has done. Tangun’s legacy held fast among the Korean people long before the introduction of Confucian or Buddhist ideas, which probably gave new depth and color to long extant Korean values.

The enormous drive to succeed and the remarkable economic transformation of South Korea might be seen as an expression of the drive to constantly succeed and bring honor to one’s family or to the Korean people as a whole. While the effects of material wealth and overindulgence is lamentable, the Korean people need not go the way of ennui, greed, neglect of the needy or overindulgence that has plagued many of the modern developed nations. We must reclaim the cultural heritage of our past and to rediscover the nobility and centrality of filial piety in Korean society.

The enormous drive to succeed and the remarkable economic transformation of South Korea might be seen as an expression of the drive to constantly succeed and bring honor to one’s family or to the Korean people as a whole. While the effects of material wealth and overindulgence is lamentable, the Korean people need not go the way of ennui, greed, neglect of the needy or overindulgence that has plagued many of the modern developed nations. We must reclaim the cultural heritage of our past and to rediscover the nobility and centrality of filial piety in Korean society.

To do this, we might look for inspiration from Tangun and his father, Hwannug. The son of the Lord of Heaven, Hwannug was moved by compassion for the people of the world, left his place in the Heavens in order to bring to them order, justice, compassion and mercy. As Hwannug’s son, Tangun substantiated his father’s act of filial devotion by establishing a kingdom on the principles passed down from father to son: the principles of Hongik Ingan. Korean society, on both sides of the current political borders, would do well to reexamine the ideals therein.