Many Koreans, especially those from the older generation, have told me that my father was truly the pioneer of opening relations between the North and South. I have heard stories of my father addressing the North Korean leadership at Mansudae, their National Assembly. According to all accounts, he spoke for two hours with force and dignity, striking the lectern at times with his fist for emphasis. He told them that, for the future good of the nation, they should abandon Juche ideology and embrace the sovereignty of God.

This was not diplomatic language, but my father spoke with complete conviction because he knew that only through such a change could those leaders save the nation. After such a speech, nobody, except my father, expected that he would be able to meet Kim Il-sung. Yet on December 6, 1991, he was invited to Kim’s official residence in Hamheung for the meeting that supposedly would never take place.

This was not diplomatic language, but my father spoke with complete conviction because he knew that only through such a change could those leaders save the nation. After such a speech, nobody, except my father, expected that he would be able to meet Kim Il-sung. Yet on December 6, 1991, he was invited to Kim’s official residence in Hamheung for the meeting that supposedly would never take place.

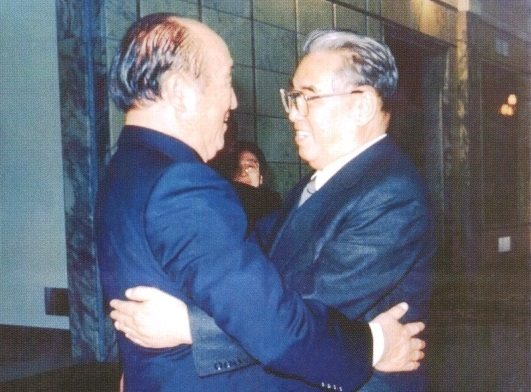

Upon seeing Kim Il-Sung my father did not bow formally or shake hands politely but embraced Kim Il-sung like a long-lost brother. At the same time, he repeated the message he had given at the National Assembly and urged Kim to give up his nuclear project and to allow in international inspectors. He also asked Kim to begin a process of peaceful unification with the simple, human step of allowing family reunions.

Later, during an intimate moment, my father told me that this meeting had been the hardest thing he had ever done in his life. It was not concern for his own safety that he wrestled with but the challenge of embracing, without reservation, a man who had not only plotted against my father’s life but had visited untold suffering on the Korean people and nation. Yet, he told me, he felt compelled by God to digest his personal feelings in order to open a door into North Korea.

Through his absolute conviction and complete commitment to this mission, my father possessed a moral authority that moved Kim Il-sung in a way that military force or economic inducements never could. Some time ago in Korea I met Congressman Cho Myung-chul, the first defector from North Korea to become a member of the National Assembly. I was surprised to learn from him that his father, who had been a government minister in North Korea, had been present at the meeting between my father and Kim Il-sung. His father told him that Kim had been deeply moved by my father and had opened his heart to him. Kim told his staff afterward that Reverend Moon was the only person outside North Korea whom he could trust.

These experiences are my inheritance. My father’s life, my memories of him, the things he spoke to me about in private moments, have all left an indelible imprint on my life. As his eldest living son I am compelled to carry on his legacy, a legacy that is inextricably tied to the destiny of the Korean people and the Korean nation. For me, that destiny lies with a unified Korea that lives up to its providential destiny.

This is reflection by Dr. Hyun Jin Preston Moon on his father’s visit to North Korea in December 6, 1991. Dr. Moon has a legacy connected to the issue of Korean reunification that spans generations which he mentions in his book Korean Dream: A Vision of a Unified Korea. The book outlines an approach to Korean reunification that urges Koreans to claim a shared vision and values for their people. The book is available for purchase on Amazon.com.