Connecting Dreams

In Korean Dream: A Vision for a Unified Korea, Dr. Hyun Jin Preston Moon explores the dreams of Genghis Khan and America at the time of its founding. In these explorations of two very distinct cultures, Dr. Moon identifies key principles that could inform Korea in its own search for a way forward on the Korean peninsula.

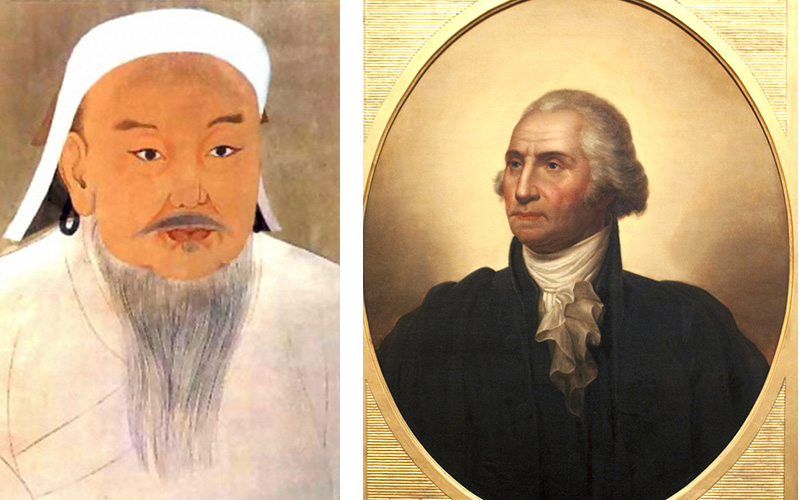

Genghis Khan and the U.S. Founding Fathers

Depictions of Genghis Khan (left) and George Washington (right)

Most people don’t see a link between the infamous conqueror, Genghis Khan, and George Washington. But in fact, Khan influenced Washington in ways we are only now really beginning to appreciate.

Significantly for us today, Khan and Washington saw eye-to-eye on one particularly important issue on the relationship between religion and politics. I.e., they both understood the importance of religion and religious freedom to the health and well-being of a society.

In his farewell address in 1789, George Washington remarked, “Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports.”

And while in the Western world, the name Genghis Khan has for centuries represented barbarity incarnate, many would be shocked to learn that Genghis Khan’s Mongolian Empire was studied by the American Founding Fathers. At the time, would-be presidents such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson debated, discussed and studied historical models as they worked to realize a nation governed by its people for the first time in world history. And as the emerging nation grappled with the ‘problem’ of religious diversity – they looked to the Mongolian Empire.

Scholar Jack Weatherford details these links in his book, Genghis Khan and the Quest for God. At its height, the Mongolian Empire stretched across Europe and Asia and conquered roughly 3 billion people, most of the known world. Amidst every imaginable kind of diversity, the Mongolian Empire oversaw one of the most peaceable periods known to mankind, dubbed Pax Mongolica.

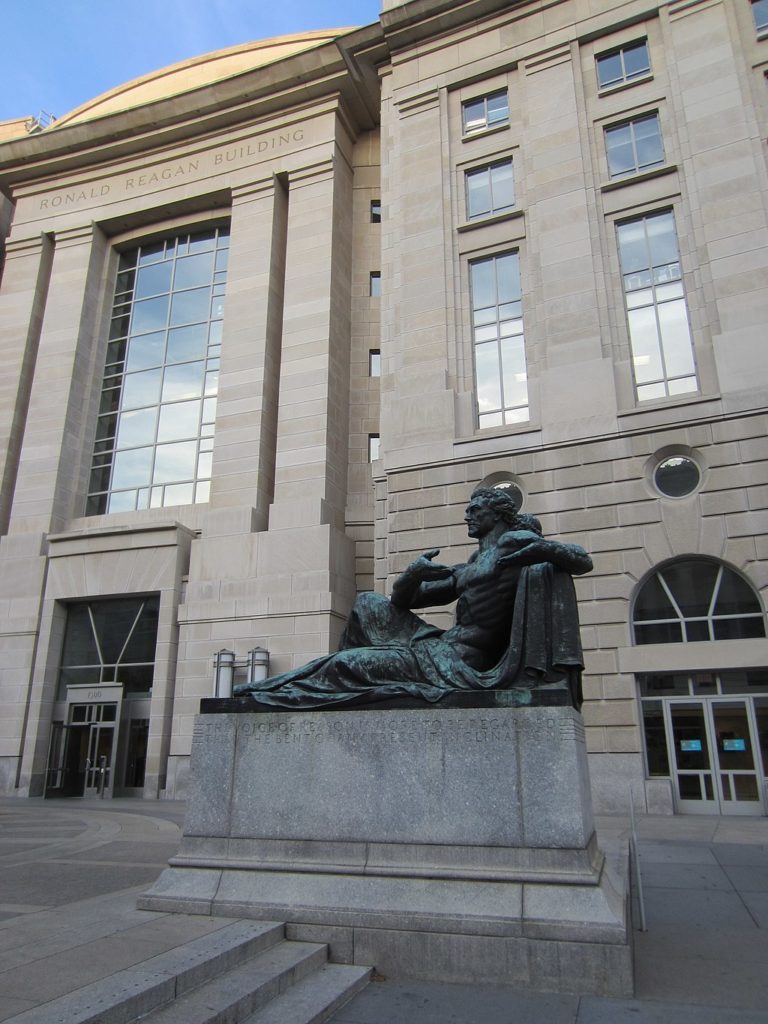

Statue in front of Reagan Building in Washington D.C. reads “Our liberty of worship is not a concession nor a privilege, but an inherent right.”

Knowing this, the American Founding Fathers chose to learn from this period by instituting religious freedom as well as granting religious institutions tax exemptions, as Genghis Khan had done. In most of history, religion was instituted from above and the populace was expected to follow accordingly. Forced conversion and persecution for having a minority faith was a routine business at the time. The great gamble both the Great Khan and the U.S. Founding Fathers took was in allowing and facilitating grassroots, local populations to determine their own faith so long as they followed the laws of the land.

More remarkable still were the tax exemptions, which reinforced the government’s commitment to serve the people, rather than the other way around. These exemptions acknowledged and encourages religious institutions to flourish and as we saw in the American colonies, religious communities spread and blossomed across the nation well into the present day.

The American religious landscape has also worked to improve religious communities in general. By creating what essentially became a “marketplace” for religions, religious institutions needed to then serve the needs and interests of its congregants. Where they did not, the numbers dwindled as there were plenty of other options to take its place. These developments had since led to a flourishing that, interestingly enough, we see now taking place across the developing world as a globally more tolerant religious landscape has challenged religious orthodoxy in important ways.

In these unforeseeable ways, the lessons for one people, one nation, can become models for others to learn from. As nations today face the challenge of building a “unity in diversity” the lessons of one society can have a profound and powerful impact on other nations. Moving forward, the U.S. needs to look back on the aspirations it cast at its founding as a free, self-governing society. In this look back, we encourage a hard, long look at the role of religions, morality and their relationships with a free Republic.

As Benjamin Franklin once quipped, the U.S. is a “republic, if you can keep it.”

How will we keep it? What do we need and where do we go to engage in these critical conversations about the future of our nation?