“As I reflect on the memories of my father, I think of the Korean people, who, like the salmon, need to return to their original hometown, the place of their birth to begin the next cycle of life. That place begins with our founding mythology of Dangun and is expressed throughout the history of our people in the principles of Hong-ik Ingan. It finds purpose and meaning in the Korean Dream to be a unique, united and independent sovereign nation that can realize our providential destiny to serve and “benefit all of humanity.”

-Hyun Jin Preston Moon – Korean Dream: A Vision for a Unified Korea

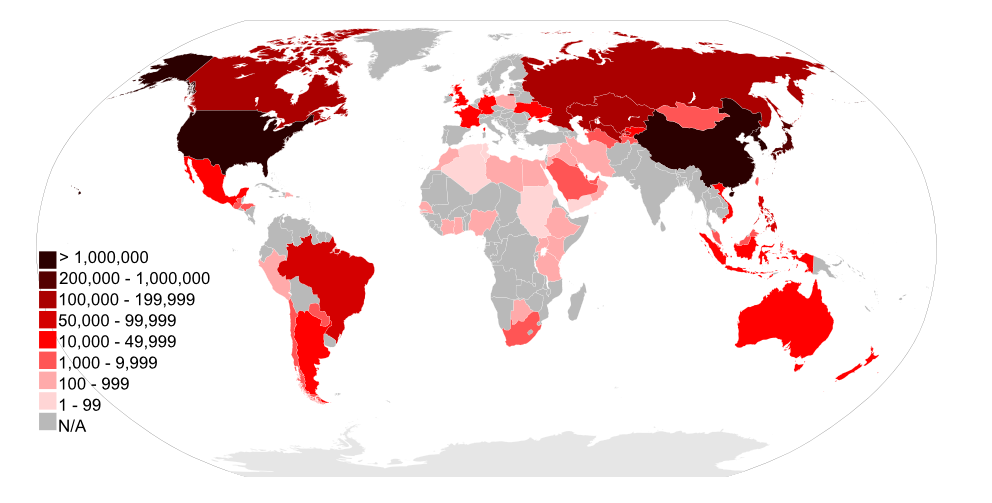

Conversations about Korean identity become considerably complex and interesting when taking in account of the Korean Diaspora. Estimated at over 7 million, large and small groups of Koreans have settled across all seven continents and hundreds of countries around the world. Some have worked to retain the Korean language, culture and familial systems while others have acclimated to those of their host country. Some left generations ago, others a few months or years ago and for a myriad of different reasons and circumstances. Some have prospered and others have suffered.

One can imagine that, in traveling hundreds, thousands or even only a few miles outside of the familiar, one might find one’s self more clearly because of the difference. When something as seemingly mundane as the weather also shifts norms in terms of available food, preferred attire, etc, it might make that of the home country all the more distinctive. We can only imagine how it might affect self-understanding in other ways. The rise of Korean Studies at universities from Oxford, the Center for Korea Research at Columbia University and institutes, such as the East Rock Institute in New Haven, CT and many, many others are testaments to this idea.

The Korean Diaspora has had much to offer the peninsula in the past century and a half. The Korean independence movement during the Japanese colonial period was greatly affected and informed by those Koreans living outside of the country. Woodrow Wilson’s 14 Point Declaration, in spite of actual U.S. foreign policy towards Korea itself, inspired a group of young Korean expat visionaries to bring freedom and self-determination to the Korean fatherland. In the 1970s and 80s, the Korean Diaspora also played a role in encouraging the burgeoning pro-democracy movement.

In reflecting on these, one is inclined to invite this same group to contribute then to a vision of a reunified Korea. In some sense, perhaps it is in interacting with the diversity of the world that people of the Korean Diaspora might understand Korea in a way apart from those who have never left. Efforts to retain the best of one’s home culture can be separated out from less helpful aspects that are easier to ascertain in new contexts.

One might hope that in engaging both domestic and expat Korean communities across the globe, we can rediscover our own distinctive identity, history, principles and values to reclaim the Korean destiny and bring “benefit to all humanity.”

To learn more, visit: Korean Dream